【文献名】

著者名:O’Flynn N, Staniszewska S et al.

文献タイトル:Improving the experience of care for people using NHSserveices; summary of NICE guidance.

雑誌名・書籍名:BMJ.

発行年:10.1136/bmj.d6422.

【要約】

The emphasis in healthcare has often been on clinical efficacy and outcomes, which can come at the expense of the patient’s experience. Developments in healthcare delivery can make giving attention to the individual more difficult, especially as healthcare has become more technological and specialised, increasing the number of people and services that a patient has contact with. Changes in the working practices of healthcare staff (such as more part time working) and the rise in the number of large institutions delivering care can mean that patients have less opportunity to develop relationships with professionals who treat them and are more likely to be treated by a team.

The NHS “next stage” review, a review commissioned to develop a vision of an NHS fit for the 21st century, recognised the experience of patients as one of three dimensions of quality.1 The other two dimensions were clinical effectiveness and safety.

<Essential requirements of care>

・Do not discuss the patient in their presence without involving them in the discussion.

・Be prepared to raise sensitive issues (such as sexual activity, continence care, and end of life) as these will not be raised by some patients.

・Ensure that the patient’s nutrition and hydration are adequate at all times (when they are unable to manage this themselves) by:

Providing regular food and fluid of adequate quantity and quality in an environment conducive to eatingPlacing food and drink where the patient can reach them easily

Encouraging and helping the patient to eat and drink if needed

Providing appropriate support, such as modified eating aids and/or drinking aids.

・Ensure that the patient’s pain relief is adequate at all times when they are unable to manage their own analgesia by: Not assuming that the patient’s pain relief is adequate

Asking the patient regularly about pain

Assessing pain using a pain scale if necessary

Providing pain relief regularly and adjusting as needed.

・When the patient is unable to manage their own personal needs (for example, relating to continence, personal hygiene, and comfort), inquire regularly and try to meet such needs at the time of asking. Ensure maximum privacy.

<Shared decision making>

・When trying to reach a shared decision on investigations and treatment, discuss the matter in a style and manner that enables the patient to express their personal needs and preferences.

・Give the patient the opportunity to discuss their diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment.

・Before starting any investigations or treatment: Explain the medical aims of the proposed care

Openly discuss and provide information about the risks, benefits, and consequences of the investigation or treatment (taking into account factors such as coexisting conditions and the patient’s preferences)

Set aside adequate time to allow any questions to be answered, and ask the patient if they would like a further consultation.

・Clarify what the patient hopes the treatment will achieve and discuss any misconceptions.

・Give the patient, and their family members and/or carers if appropriate, adequate time to decide whether they wish to have investigations and/or treatment.

・Accept and acknowledge that patients may vary in their views about the balance of risks, benefits, and side effects of treatments.

・Use the following principles when discussing risks and benefits with a patient:

Personalise risks and benefits as far as possible..

Use absolute risk rather than relative risk–for example, the risk of an event increases from 1 in 1000 to 2 in 1000, rather than the risk of the event doubles.

Use natural frequency rather than a percentage–for example, 10 in 100 (better still, 1 in 10) rather than 10%.

Be consistent in the use of data–for example, use the same denominator when comparing risk: 7 in 100 for one risk and 20 in 100 for another, rather than 1 in 14 and 1 in 5

.

Present a risk over a defined period of time (months or years) if appropriate–for example, if 100 people are treated for 1 year, 10 will experience a given side effect.

Include both positive and negative framing–for example, treatment will be successful for 97 out of 100 patients and unsuccessful for 3 out of 100 patients.

People differ in the way they interpret terms such as rare, unusual, and common, so use numerical data if available.

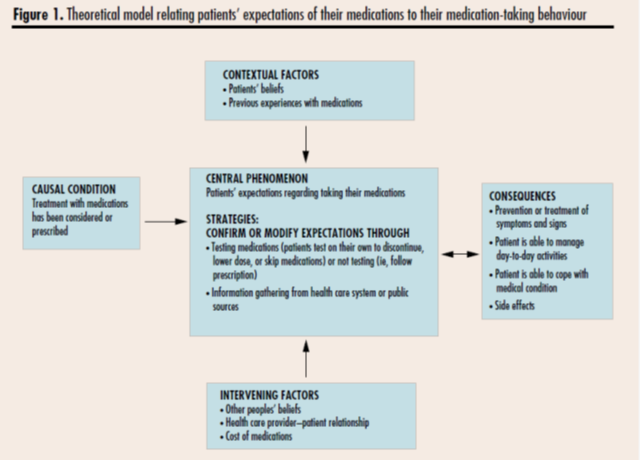

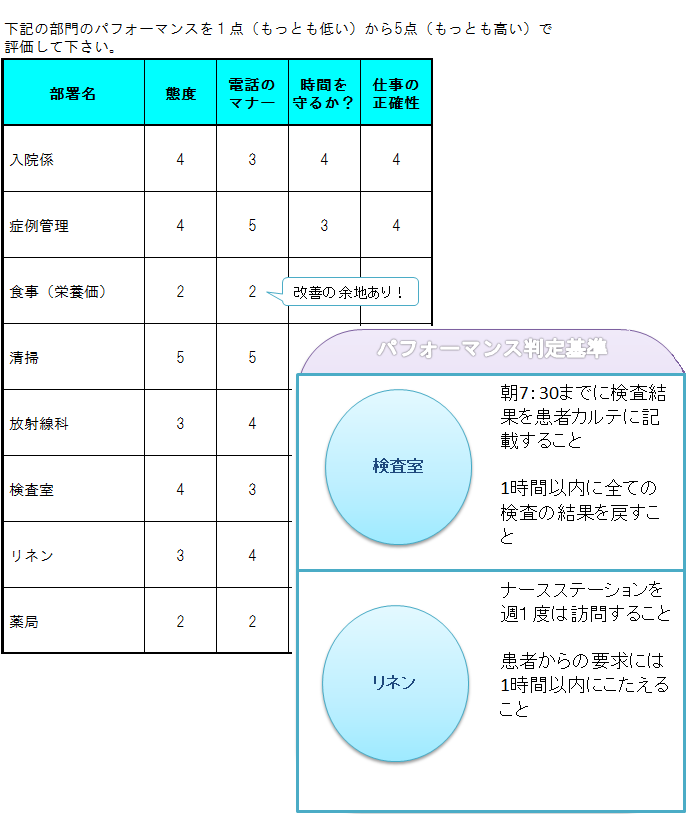

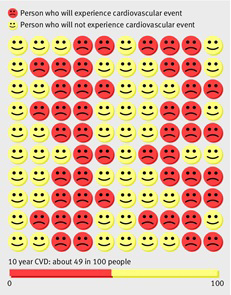

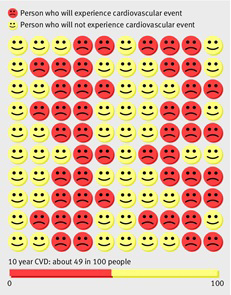

Consider using a mixture of numerical and pictorial formats–for example, numerical rates and pictograms (such as figures 1 and 2).

・Offer support to the patient when they are considering options. Use the principles of shared decision making: Ensure that the patient is aware of the options available, and explain the risks, benefits, and consequences of these.

Check that the patient understands the information.

Encourage the patient to clarify what is important to them, and check that their choice is consistent with this.

・Be aware of the value and availability of patient based decision aids. If suitable high quality decision aids are available, offer the most appropriate one to the patient.

<Tailoring healthcare services to the patient>

・At intervals agreed with the patient, review their knowledge, understanding, and concerns about their condition and treatments, and their view of their need for treatment, as these may change over time. Offer the patient repeat information and review, especially when treating a long term condition.

・Tailor healthcare services to the patient’s needs and circumstances, taking into account locality, access, personal preferences, and coexisting conditions. Review the patient’s needs and circumstances regularly.

・Give the patient information about relevant and available treatment options even if these are not provided locally.

・Tell the patient about available health and social services (such as smoking cessation services) and encourage them to access these according to their individual needs.

・Ensure that discussions are held in a way that allows the patient to express their personal needs and preferences for care. Allow adequate time so that discussions do not feel rushed.

・Clarify with the patient at the outset whether and how they would like their spouse, partner, family members, and/or carers to be involved in key decisions about the management of their condition.

・Accept that the patient may have different views from healthcare professionals about the balance of risks, benefits, and consequences of treatments.

・Accept that the patient has the right to decide not to have a treatment (even if you do not agree with the decision) as long as he or she has the capacity to make an informed decision and has been given the information needed to do this.

・Inform the patient that they have a right to a second opinion.

・Respect and support the patient in their choice of treatment or decision to decline treatment.

・When patients in hospital are taking medicines for long term conditions, consider and discuss with them whether they are able to, and would prefer to, manage these medicines themselves.

<Continuity of care>

・Consider each patient’s requirement for continuity of care and how that requirement will be met. This may involve the patient seeing the same healthcare professional throughout a single episode of care or ensuring continuity within a healthcare team.

・Inform the patient about:

Who is responsible for their care and treatment

The roles and responsibilities of the different members of the healthcare team

The communication that takes place between members of the healthcare team.

・Give the patient (and their family members and/or carers if appropriate) information about what to do and whom to contact in different situations, such as “out of hours” or in an emergency.

・For patients who need several different services, ensure effective coordination and prioritisation of care to minimise the impact on the patient.

・Ensure clear and timely exchange of patient information between healthcare professional teams and other agencies–for example, transitions of care including discharge.

Fig 1 Personalised pictogram and bar chart based on high quality predictive models showing that of 100 patients with particular clinical characteristics 49 will experience a cardiovascular event (such as a heart attack or stroke) over the next 10 years. Adapted with permission from the Institute of Health and Society, Newcastle University

Fig 2 Personalised pictogram and bar chart showing the likely reduction in risk of cardiovascular events after stopping smoking, reduced from 49 in 100 to 31 in 100. Adapted with permission from the Institute of Health and Society, Newcastle University

【開催日】

2012年4月4日